Without a Doubt: "Faith, Certainty and the Presidency of George W. Bush"

Without a Doubt: "Faith, Certainty and the Presidency of George W. Bush"

Ron Suskind, New York Times (Magazine section), October 17, 2004

Bruce Bartlett, a domestic policy adviser to Ronald Reagan and a treasury official for the first President Bush, told me recently that ''if Bush wins, there will be a civil war in the Republican Party starting on Nov. 3.''

The nature of that conflict, as Bartlett sees it?

Essentially, the same as the one raging across much of the world: a battle between modernists and fundamentalists, pragmatists and true believers, REASON and RELIGION.

Just in the past few months,'' Bartlett said, ''I think a light has gone off for people who've spent time up close to Bush: that this instinct he's always talking about is this sort of weird, Messianic idea of what he thinks God has told him to do.''

Bartlett, a 53-year-old columnist and self-described libertarian Republican who has lately been a champion for traditional Republicans concerned about Bush's governance,

went on to say: ''This is why George W. Bush is so clear-eyed about Al Qaeda and the Islamic fundamentalist enemy. He believes you have to kill them all. They can't be persuaded, that they're extremists, driven by a dark vision. He understands them, because he's just like them. . . .

This is why he dispenses with people who confront him with inconvenient facts,'' Bartlett went on to say. ''He truly believes he's on a mission from God. Absolute faith like that overwhelms a need for analysis.

The whole thing about faith is to believe things for which there is no empirical evidence.'' Bartlett paused, then said, ''But you can't run the world on faith.''

[... ...]

... policies that often seemed to collide with accepted facts. The president would say that he relied on his ''gut'' or his ''instinct'' to guide the ship of state, and then he ''prayed over it.''

The old pro Bartlett, a deliberative, fact-based wonk, is finally hearing a tune that has been hummed quietly by evangelicals (so as not to trouble the secular) for years as they gazed upon President George W. Bush.

This evangelical group -- the core of the energetic ''base'' that may well usher Bush to victory -- believes that their leader is a messenger from God.

And in the first presidential debate, many Americans heard the discursive John Kerry succinctly raise, for the first time, the issue of Bush's certainty -- the issue being, as Kerry put it, that ''you can be certain and be wrong.''

What underlies Bush's certainty? And can it be assessed

in the temporal realm of informed consent?

All of this -- the ''gut'' and ''instincts,'' the certainty and religiosity

-connects to a single word, ''faith,'' and faith asserts its hold ever more on debates in this country and abroad.

That a deep Christian faith illuminated the personal journey of George W. Bush is common knowledge.

But faith has also shaped his presidency in profound, nonreligious ways. The president has demanded unquestioning faith from his followers, his staff, his senior aides and his kindred in the Republican Party. Once he makes a decision -- often swiftly, based on a creed or moral position -- he expects complete faith in its rightness.

The disdainful smirks and grimaces that many viewers were surprised to see in the first presidential debate are familiar expressions to those in the administration or in Congress who have simply asked the president to explain his positions.

Since 9/11, those requests have grown scarce; Bush's intolerance of doubters has, if anything, increased, and few dare to question him now. A writ of infallibility -- a premise beneath the powerful Bushian certainty that has, in many ways, moved mountains -- is not just for public consumption: it has guided the inner life of the White House.

[... ...]

The faith-based presidency is a with-us-or-against-us model that has been enormously effective at, among other things, keeping the workings and temperament of the Bush White House a kind of state secret. ... ...

... ... When I quoted O'Neill saying that Bush was like ''a blind man in a room full of deaf people,'' this did not endear me to the White House. But my phone did begin to ring, with Democrats and Republicans calling with similar impressions and anecdotes about Bush's faith and certainty. These are among the sources I relied upon for this article.

Few were willing to talk on the record. Some were willing to talk because they said they thought George W. Bush might lose; others, out of fear of what might transpire if he wins.

In either case, there seems to be a growing silence fatigue -- public servants,

some with vast experience,who feel they have spent years being treated like Victorian-era children, seen but not heard, and are tired of it.

... ... Some officials, elected or otherwise, with whom I have spoken with left meetings in the Oval Office concerned that the president was struggling with the demands of the job.

Others focused on Bush's substantial interpersonal gifts as a compensation for his perceived lack of broader capabilities.

Still others, like Senator Carl Levin of Michigan, a Democrat, are worried about something other than his native intelligence. ''He's plenty smart enough to do the job,'' Levin said. ''It's his lack of curiosity about complex issues which troubles me.'' But more than anything else, I heard expressions of awe at the president's preternatural certainty and wonderment about its source.

There is one story about Bush's particular brand of certainty I am able to piece together and tell for the record.

In the Oval Office in December 2002, the president met with a few ranking senators and members of the House, both Republicans and Democrats. In those days, there were high hopes that the United States-sponsored ''road map'' for the Israelis and Palestinians would be a pathway to peace, and the discussion that wintry day was, in part, about countries providing peacekeeping forces in the region.

The problem, everyone agreed, was that a number of European countries, like France and Germany, had armies that were not trusted by either the Israelis or Palestinians.

One congressman -- the Hungarian-born Tom Lantos, a Democrat from California and the only Holocaust survivor in Congress -- mentioned that the Scandinavian countries were viewed more positively. Lantos went on to describe for the president how the Swedish Army might be an ideal candidate to anchor a small peacekeeping force on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip.

Sweden has a well-trained force of about 25,000.The president looked at him appraisingly, several people in the room recall. ''I don't know why you're talking about Sweden,''

Bush said. ''They're the neutral one. They don't have an army.''Lantos paused, a little shocked, and offered a gentlemanly reply: ''Mr.

President, you may have thought that I said Switzerland. They're the ones that are historically neutral, without an army.'' Then Lantos mentioned, in a gracious aside, that the Swiss do have a tough national guard to protect the country in the event of invasion.Bush held to his view. ''No, no, it's Sweden that has no army.''

The room went silent, until someone changed the subject.

A few weeks later, members of Congress and their spouses gathered with administration officials and other dignitaries for the White House Christmas party.

The president saw Lantos and grabbed him by the shoulder. ''You were right,'' he said, with bonhomie. ''Sweden does have an army.''

This story was told to me by one of the senators in the Oval Office that December day, Joe Biden.

Lantos, a liberal Democrat, would not comment about it. In general, people who meet with Bush will not discuss their encounters. (Lantos, through a spokesman, says it is a longstanding policy of his not to discuss Oval Office meetings.)

... ...

In the summer of 2002, after I had written an article in Esquire that the White House didn't like about Bush's former communications director, Karen Hughes, I had a meeting with a senior adviser to Bush. He expressed the White House's displeasure, and then he told me something that at the time I didn't fully comprehend -- but which I now believe gets to the very heart of the Bush presidency.

The aide said that guys like me were ''in what we call the reality-based community,''

which-- he defined as people who ''believe that solutions emerge from your judicious study of discernible reality.''

I nodded and murmured something about enlightenment principles and empiricism.

He cut me off. ''That's not the way the world really works anymore,'' he continued. ''We're an empire now, and when we act, we

create our own reality. And while you're studying that reality --

judiciously, as you will -- we'll act again, creating other new realities, which you can study too, and that's how things will sort out.We're history's actors . . . and you, all of you, will be left to just

study what we do.''

Who besides guys like me are part of the reality-based community? Many of the other elected officials in Washington, it would seem.

A group of Democratic and Republican members of Congress were called in to discuss Iraq-- sometime before the October 2002 vote authorizing Bush to move forward.

A Republican senator recently told Time Magazine that the president walked in and said: ''Look, I want your vote. I'm not going to debate it with you.'' When one of the senators began to ask a question, Bush snapped, ''Look, I'm not going to debate it with you.''

The 9/11 commission did not directly address the question of whether Bush exerted influence over the intelligence community about the existence of weapons of mass destruction. That question will be investigated after the election, but if no tangible evidence of undue pressure is found, few officials or alumni of the administration whom I spoke to are likely to be surprised.

''If you operate in a certain way -- by saying this is how I want to justify what I've already decided to do, and I don't care how you pull it off -- you guarantee that you'll get faulty, one-sided information,'' Paul O'Neill, who was asked to resign his post of treasury secretary in December 2002, said when we had dinner a few weeks ago. ''You don't have to issue an edict, or twist arms, or be overt.''

In a way, the president got what he wanted:

--a National Intelligence Estimate on W.M.D. that creatively marshaled a few thin facts, and then Colin Powell putting his credibility on the line at the United Nations in a show of faith.

That was enough for George W. Bush to press forward and invade Iraq.

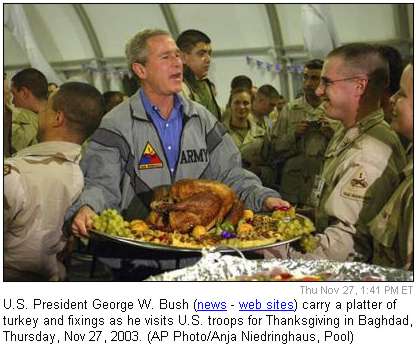

As he told his quasi-memoirist, Bob Woodward, in ''Plan of Attack'': ''Going into this period, I was praying for strength to do the Lord's will. . . . I'm surely not going to justify the war based upon God. Understand that. Nevertheless, in my case, I pray to be as good a messenger of his will as possible.''

Machiavelli's oft-cited line about the adequacy of the perception of power prompts a question. Is the appearance of confidence as important as its possession? Can confidence -- true confidence -- be willed? Or must it be earned?

George W. Bush, clearly, is one of history's great confidence men.

That is not meant in the huckster's sense, though many critics claim that on the war in Iraq, the economy and a few other matters he has engaged in some manner of bait-and-switch.

No, I mean it in the sense that he's a believer in the power of confidence. At a time when constituents are uneasy and enemies are probing for weaknesses, he clearly feels that unflinching confidence has an almost mystical power. It can all but create reality.

Whether you can run the world on faith, it's clear you can run one hell of a campaign on it.

[... ...]

A recent Gallup Poll noted that 42 percent of Americans identify themselves as evangelical or ''born again.''

While this group leans Republican, it includes black urban churches and is far from monolithic. But Bush clearly draws his most ardent supporters and tireless workers from this group, many from a healthy subset of approximately four million evangelicals who didn't vote in 2000 -- potential new arrivals to the voting booth who could tip a close election or push a tight contest toward a rout.

This signaling system -- forceful, national, varied, yet clean of the

president's specific fingerprint -- carries enormous weight.

Lincoln Chafee, the moderate Republican senator from Rhode Island, has broken with the president precisely over concerns about the nature of Bush's certainty. ''This issue,'' he says, of Bush's ''announcing that 'I carry the word of God' is the key to the election. The president wants to signal to the base with that message, but in the swing states he does not.''

Come to the hustings on Labor Day and meet

the base.

In 2004, you know a candidate by his base,

and

the Bush campaign is harnessing the might of churches, with hordes

of voters

registering through church-sponsored programs.

Following the news

of Bush on his national tour in the week after

the Republican convention, you

could sense how a faith-based president

campaigns: on a surf of prayer and

righteous rage.

Righteous rage -- that's what Hardy Billington felt when he heard about same-sex marriage possibly being made legal in Massachusetts. ''It made me upset and disgusted, things going on in Massachusetts,'' the 52-year-old from Poplar Bluff, Mo., told me. ''I prayed, then I got to work.''

Billington spent $830 in early July to put up a billboard on the edge of town. It read: ''I Support President Bush and the Men and Women Fighting for Our Country. We Invite President Bush to Visit Poplar Bluff.'' Soon Billington and his friend David Hahn, a fundamentalist preacher, started a petition drive. They gathered 10,000 signatures. That fact eventually reached the White House scheduling office.

By late afternoon on a cloudy Labor Day, with a crowd of more than 20,000 assembled in a public park, Billington stepped to the podium. ''The largest group I ever talked to I think was seven people, and I'm not much of a talker,'' Billington, a shy man with three kids and a couple of dozen rental properties that he owns, told me several days later. ''I've never been so frightened.''

But Billington said he ''looked to God'' and said what was in his heart.

''The United States is the greatest country in the world,'' he told

the rally. ''President Bush is the greatest president I have ever known.

I love my president.

I love my country.

And more important, I love Jesus Christ.''

The crowd went wild, and they went wild again when the president finally arrived and gave his stump speech. There were Bush's periodic stumbles and gaffes, but for the followers of the faith-based president, that was just fine. They got it -- and ''it'' was the faith.

And for those who don't get it?

That was explained to me in late 2002 by Mark McKinnon, a longtime senior media adviser to Bush, who now runs his own consulting firm and helps the president.

He started by challenging me. ''You think he's an idiot, don't you?'' I said, no, I didn't. ''No, you do, all of you do, up and down the West Coast, the East Coast, a few blocks in southern Manhattan called Wall Street.

"Let me clue you in. We don't care. You see, you're outnumbered 2 to 1 by folks in the big, wide middle of America, busy working people who don't read The New York Times or Washington Post or The L.A. Times.

"And you know what they like? They like the way he walks and the way he points, the way he exudes confidence. They have faith in him. And when you attack him for his malaprops, his jumbled syntax, it's good for us.

"Because you know what those folks don't like? They don't like you!''

In this instance, the final ''you,'' of course, meant the entire reality-based community.

Thee bond between Bush and his base is a bond of mutual support.

He supports them with his actions, doing his level best to stand firm on wedge issues like abortion and same-sex marriage while he identifies evil in the world, at home and abroad.

They respond with fierce faith. The power of this transaction is something that people, especially those who are religious, tend to connect to their own lives.

If you have faith in someone, that person is filled like a vessel. Your faith is the wind beneath his or her wings. That person may well rise to the occasion and surprise you: I had faith in you, and my faith was rewarded. Or, I know you've been struggling, and I need to pray harder.

Bush's speech that day in Poplar Bluff finished with a mythic appeal: ''For all Americans, these years in our history will always stand apart,'' he said. ''You know, there are quiet times in the life of a nation when little is expected of its leaders.

This isn't one of those times. This is a time that needs -- when we need firm resolve and clear vision and a deep faith in the values that make us a great nation.''

The life of the nation and the life of Bush effortlessly merge -- his fortitude, even in the face of doubters, is that of the nation; his ordinariness, like theirs, is heroic; his resolve, to whatever end, will turn the wheel of history.

Remember, this is consent, informed by the heart and by the spirit. In the end, Bush doesn't have to say he's ordained by God. After a day of speeches by Hardy Billington and others, it goes without saying.

''To me, I just believe God controls everything, and God uses the president to keep evil down, to see the darkness and protect this nation,'' Billington told me, voicing an idea shared by millions of Bush supporters.

''Other people will not protect us. God gives people choices to make. God gave us this president to be the man to protect the nation at this time.''

But when the moment came in the V.I.P. tent to shake Bush's hand, Billington remembered being reserved. '''I really thank God that you're the president' was all I told him.'' Bush, he recalled, said, ''Thank you.''

''He knew what I meant,'' Billington said. ''I believe he's an instrument of God, but I have to be careful about what I say, you know, in public.''

Is there anyone in America who feels that John Kerry is an instrument of God?

''I'm going to be real positive, while I keep my foot on John Kerry's throat,'' George W. Bush said last month at a confidential luncheon a block away from the White House with a hundred or so of his most ardent, longtime supporters, the so-called R.N.C. Regents.

This was a high-rolling crowd -- at one time or another, they had all given large contributions to Bush or the Republican National Committee. Bush had known many of them for years, and a number of them had visited him at the ranch. It was a long way from Poplar Bluff.

The Bush these supporters heard was a triumphal Bush, actively beginning to plan his second term. It is a second term, should it come to pass, that will alter American life in many ways, if predictions that Bush voiced at the luncheon come true. ... ...

According to notes provided to me, and according to several guests at the lunch who agreed to speak about what they heard, he said that ''Osama bin Laden would like to overthrow the Saudis . . .

then we're in trouble. Because they have a weapon. They have the oil.''

He said that there will be an opportunity to appoint a Supreme Court justice shortly after his inauguration, and perhaps three more high-court vacancies during his second term.

''Won't that be amazing?'' said Peter Stent, a rancher and conservationist who attended the luncheon. ''Can you imagine? Four appointments!''

After his remarks, Bush opened it up for questions, and someone asked what he's going to do about energy policy with worldwide oil reserves predicted to peak.

Bush said: ''I'm going to push nuclear energy, drilling in Alaska and clean coal. Some nuclear-fusion technologies are interesting.'' He mentions energy from ''processing corn.''

''I'm going to bring all this up in the debate, and I'm going to push it,'' he said, and then tried out a line. ''Do you realize that ANWR [the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge] is the size of South Carolina, and where we want to drill is the size of the Columbia airport?''

The questions came from many directions -- respectful, but clearly reality-based.

About the deficits, he said he'd ''spend whatever it takes to protect our kids in Iraq,'' that ''homeland security cost more than I originally thought.''

In response to a question, he talked about diversity, saying that ''hands down,'' he has the most diverse senior staff in terms of both gender and race. He recalled a meeting with Chancellor Gerhard Schröder of Germany. ''You know, I'm sitting there with Schröder one day with Colin and Condi. And I'm thinking: What's Schröder thinking?! He's sitting here with two blacks and one's a woman.''

But as the hour passed, Bush kept coming back to the thing most on his mind: his second term.

''I'm going to come out strong after my swearing in,'' Bush said, ''with fundamental tax reform, tort reform, privatizing of Social Security.''

The victories he expects in November, he said, will give us ''two years, at least, until the next midterm. We have to move quickly, because after that I'll be quacking like a duck.''

... A regent I spoke to later and who asked not to be identified told me: ''I'm happy he's certain of victory and that he's ready to burst forth into his second term, but it all makes me a little nervous.

There are a lot of big things that he's planning to do domestically, and who knows what countries we might invade or what might happen in Iraq.

But when it gets complex, he seems to turn to prayer or God rather than digging in and thinking things through.

What's that line? -- the devil's in the details. If you don't go after that devil, he'll come after you.''

Bush grew into one of history's most forceful leaders, his admirers will attest, by replacing hesitation and reasonable doubt with faith and clarity. Many more will surely tap this high-voltage connection of fervent faith and bold action. In politics, the saying goes, anything that works must be repeated until it is replaced by something better. The horizon seems clear of competitors.

... is what Jim Wallis wishes he could sit and talk about with George W. Bush. That's impossible now, he says. He is no longer invited to the White House.

''Faith can cut in so many ways,'' he said. ''If you're penitent and not triumphal, it can move us to repentance and accountability and help us reach for something higher than ourselves. That can be a powerful thing, a thing that moves us beyond politics as usual, like Martin Luther King did.

But when it's designed to certify our righteousness -- that can be a dangerous thing.

"Then it pushes self-criticism aside. There's no reflection.

''Where people often get lost is on this very point,'' he said after a moment of thought. ''Real faith, you see, leads us to deeper reflection and not -- not ever -- to the thing we as humans so very much want.''

And what is that?

''Easy certainty.''